By Scott Rosenstein

Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, I was asked to make many pandemic predictions. Some were right, some were wrong. By far the hot take that was the most wrong was my December 2020 suggestion that we were about to enter an era of--wait for it--vaccine optimism.

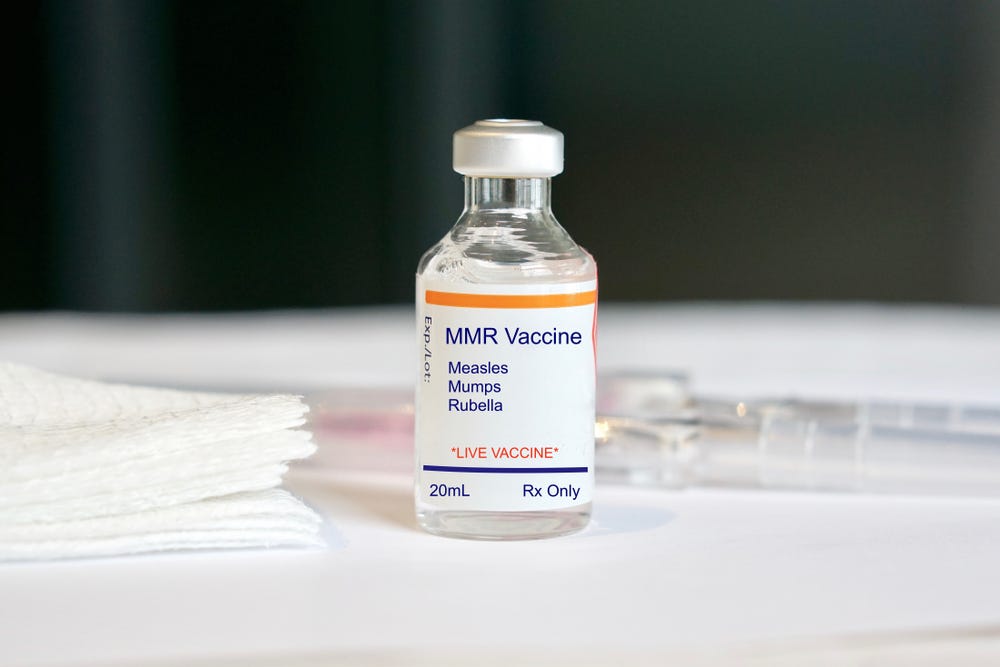

One explanation for rising vaccine skepticism has been that vaccines are a victim of their own success, particularly in the rich world. Measles was eliminated in the United States in 2000 thanks to vaccines. Communities no longer readily experience the devastation of preventable illnesses, so they are more likely to buy into incorrect epidemiological arguments that suggest the risk to a child from vaccines exceeds the risk of that illness.

Covid would change that, I thought. Vaccine clinical trial data in late 2020 exceeded even the most optimistic predictions from experts. Widespread vaccination would represent the most effective way to transition to some semblance of normal after months of human and economic suffering and highly disruptive but only somewhat effective restrictions. Firsthand experience with the power of vaccines would therefore prove to be a powerful counterargument to skeptics of other vaccines who were convinced (sometimes by Russian bots) that getting measles was better for their children than getting the measles vaccine.

Turns out there are more fans of this observation than I thought: “A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths are a statistic”—Josef Stalin.

A million people died from Covid in the United States in the first two years of the pandemic. About 75% of them were over the age of 65. And a virus that was supposedly harmless to younger people somehow killed 250,000 of them in this time—a figure that was actually higher than most worst case projections for total U.S. deaths that I saw in February 2020. And yes, more than 1,000 of these deaths were in children, a number that would seem high in other contexts but here was outdone by the fallacy of relative privation.

These statistics have obviously failed to move the needle in the United States when it comes to vaccines and the millions of lives they saved worldwide during Covid. It’s been memory holed by most people, replaced with pandemic amnesia. For others, however, Covid memories have turned to anger. Some of that anger is directed at public health officials, and some of it is legitimate—the communications misfires during Covid were real. Some of the anger is ideological and focused on mandates, playing off mistrust in government that existed pre-Covid but was amplified by the pandemic. Much of this anger, however, goes hand in hand with some really bad epidemiological arguments, leading to a rejection of Covid vaccines that were initially very good at stopping infection, transmission, and severe illness and then not so good at the first two but very good at the third (a prediction made by many experts at the time that clearly didn’t penetrate the Covid discourse).

The result of all of this was thousands of preventable deaths in the United States in 2021 and beyond and increasing skepticism of all vaccines (albeit in some communities more than others).

And yet there are some grim but vague signals that an era of--wait for it--vaccine optimism, might be upon us.

A severe measles outbreak in mostly unvaccinated children has claimed one child’s life and put 22 children in the hospital.

There are early signs that this has sparked renewed vaccination interest from formerly hesitant parents in Texas. There’s similar evidence from previous outbreaks overseas.

But people are really dug in these days. And I’m not so naive (or ready to endorse Stalinism) to think this outbreak could turn the tide nationally.

Unfortunately, there will likely need to be more suffering for that to happen.

The vaccine skeptics that have taken over the machinery of the U.S. health care system seem to have mixed feelings about that. Though there was some speculation in previous weeks that they would tread lightly around childhood vaccination, that did not appear to be the case before this outbreak began making headlines. Now, the measles messaging seems to vacillate between tepid recognition of measles vaccines and overstated generalizations about alternative therapies. Baby steps?

And so perhaps measles (or whooping cough or polio) outbreaks that put a human face on this scourge could achieve what Covid failed so miserably at: demonstrating the devastating toll of childhood illnesses to an audience that was blissfully unaware of these risks.

Perhaps this is the upside of the dog catching the car. Or the ambulance chaser becoming the ambulance.

Or, perhaps tribalism, politicization, and Russian bots will again drown out an overwhelming epidemiological argument that clearly demonstrates the value of vaccines. It’s quite possible that the marketplace of ideas remains an ill-suited venue for good faith discourse on this topic thanks to years of declining trust and information anarchy. Fool me twice shame on me, I guess.

Scott Rosenstein spent 10 years at the Eurasia Group, most recently as senior public health advisor during Covid. He specializes in pandemic preparedness, the geopolitics of health, and global health governance. He is a visiting faculty member at NYU’s school of global public health.

It was dancing in the streets for myself and my senior friends when we got our first Covid shots. And it was gratitude that the government gave us free Covid boosters in the years since.

Science saves lives - so clear to me - so I still simply don't understand the anti-vaccine mentality.

In my family, a grandmother refused to get vaccinated for Covid and as a result, on doctor's advice, was kept from her first newborn grandson for the almost 6 month period that her grandson would be at risk for Covid from an unvaccinated person. The grandmother's vaccine cultish beliefs were more important than being there for her grandson's first small hand holds, wide eyes, smiles.

Our congressmen, Musk and Trump should not be allowed to legislate on that which they know little or nothing on. Further, they should be held responsible for damages they precipitate from their involvement. That includes not only drugs, but also their involvement between a person and the hospitals or health care industry. There are governing bodies who do know what they are doing overseeing these areas.