Trump’s sell-America trade

How one reckless leader undermined confidence in America in under 100 days.

By Jared Bernstein and Ryan Cummings

There’s an adage in the study of the economy’s ups and downs, otherwise known as the business cycle: healthy economic expansions don’t die of old age; they die because they’re murdered.

All signs are pointing to a crime of precisely this magnitude, and we all know who the perp is. In fewer than 100 days, President Donald Trump has, through a level of policy recklessness heretofore unseen by any president in his first three months, thoroughly squandered his inheritance of a strong economy.

As is often the case, the damage is showing up first in financial markets. The markets for stocks, bonds, currencies, and more get a lot wrong and a lot right. They’re prone to bubbles and busts, and, especially in recent years, they move up and down on fads and bets that have nothing to do with economic fundamentals.

But their utility in this context is twofold. First, though hard data reports—jobs, growth, real incomes—are the ultimate arbiters of the health of the business cycle, those data are inherently backward-looking, while financial markets look forward. Second, they quickly aggregate information about where investors around the world think things are headed in ways that affect growth, jobs, prices, and interest rates--things that matter to all of us.

In Trump’s first 100 days, financial markets have been sending clear, negative signals in reaction to his economic agenda. That doesn’t mean the markets have tanked every day, though we’ve seen enough of that to fear checking in with our retirement accounts. But the pattern has been extremely clear. When the president and his team talk about amping up the trade war, the markets sink, and vice versa.

Because there’s been a lot more amping than back-pedaling, Trump’s first 100 days for the stock market are a real standout--in the wrong direction. This figure shows the percent return of the S&P 500 for every presidential administration since the end of World War II after their first 100 days in office.

Okay, but what if the trade war is bad for markets but good for the rest of us? First, though stock ownership is heavily concentrated among the wealthy, our point above about people being too scared to check their 401(k)s is relevant here. About 60% of middle-class near-retirees have retirement accounts in the market. Second, the trade war will raise consumer prices on everyone, which is why majorities now oppose Trump’s tariffs. Third, there is no reason to believe it is a “pain-now-gain-later” play. There’s simply no evidence of advanced economies adding jobs by taxing imports, in no small part because about half of those imports are used as inputs in U.S. manufacturing. Tariffs make us less competitive, not more.

But to us, the even more important market signals are coming from somewhat less familiar assets, including bonds, currency, and gold.

The U.S. government finances its extensive debt by exchanging IOUs in the form of U.S. Treasury bonds for loans. Creditors across the globe have long considered U.S. debt about as risk-free as it gets. We’re the world’s dominant economy, with sovereign rights to the globe’s reserve currency. Yes, we’ve been prone to deep political dysfunction in recent years, but our private sector remains a global leader in productivity, making the United States the go-to place for global investments. These attributes have allowed us to reliably finance our debt at relatively low interest rates.

Which is why it is so alarming to see that, in less than three months, Trump’s economic policies—the trade war, attacks on the independence of the Federal Reserve, a forthcoming budget-busting tax cut—have unleashed what investors are calling the “sell-America” trade. American assets, specifically our debt and our currency, have shown signs of moving from a safe asset—the port you quickly tack toward in a storm—to a riskier one.

To be clear, the damage thus far is mild and probably could be reversed. The “term premium” on U.S. government debt, which is the compensation investors demand for holding risky assets over a period of time, is up 20 basis points (0.2 percent) because of the added risk associated with the president’s recklessness, isolationism, and unpredictability. Interest rates on government debt have been elevated since Trump’s “Liberation day,” but they are still lower than where they were a year ago.

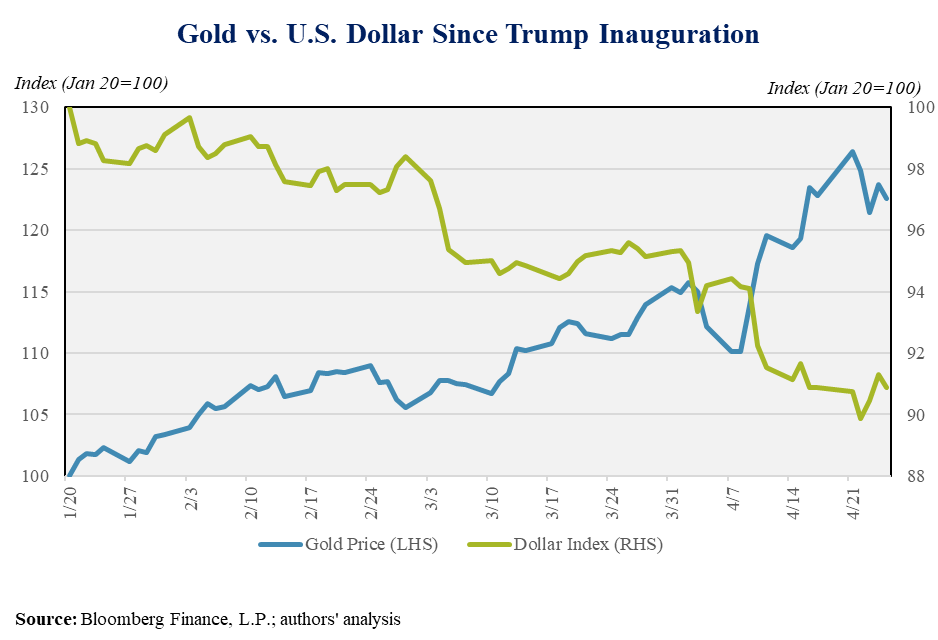

But what’s most worrisome is that the dollar is down nearly 8% since Trump took office. Of course, the dollar fluctuates frequently in response to events here and abroad. What’s different this time, though, is that in periods of economic turbulence, the dollar often rallies because the United States has been the world’s “safe haven” for financial assets. This has the effect of decreasing interest rates, which makes borrowing cheaper for American consumers, firms, and the government. But over Trump’s first 100 days, we’ve seen a reversal of this trend, with spooked investors selling the dollar, reflecting a lack of confidence in where our economy is headed under current leadership.

We’ve also been struck by how this dynamic is playing out in the market for gold. In times of severe market stress, when safe, familiar ports turn stormy, investors buy gold to hide out until the danger passes (whether this is actually a good investment strategy is another question). The figure below reveals that the Trump agenda is generating gale-force uncertainties leading to the sharpest spike on record in gold prices (up nearly 25 percent since his inauguration) while the dollar has steadily declined.

Where might all of this be headed and what does it mean for regular Americans? After all, working-class people can’t hide out in gold until the danger passes.

Along with market turmoil and the potential erosion of U.S. safe-haven status, Trump’s whiplashian pursuit of his agenda has led to significantly marked down growth expectations over the president’s first 100 days. As Bernstein shows here, real GDP growth over the first three months of 2025 is expected to come in at somewhere around zero, down from 2.4% in the previous quarter. Recession probabilities now hover around 50% or higher, conditional on whether Trump keeps blinking, which lowers the likelihood of a downturn, or doubles down, which raises it (sadly, another way of expressing this is whether Trump’s most recent conversation is with Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent or trade adviser Peter Navarro).

If domestic and global investors remain spooked about the trustworthiness of U.S. assets, i.e., if the sell-America trade persists, interest rates will remain higher than they would otherwise be, bleeding into mortgage, auto, and all other consumer loans, including credit cards. This would cause a virtuous cycle of growth to turn into a vicious cycle of contraction: the combination of higher interest rates and lower income depresses the demand for goods and services. Companies respond to lower demand by decreasing their output, so as to not have excessive inventories piling up in storage or idle workers. This, in turn, slows hiring or leads to layoffs, which leads to lower incomes.

That’s a lot of “ifs.” And we want to be careful to stress two key points: One, as we discussed at the top of this post, the underlying economy that Trump inherited was very solid; in fact, the strongest among all the advanced economies; and, two, it takes a lot of sustained, terrible policy to turn that around.

But we frankly have never seen so much self-inflicted damage done so quickly. It’s usually a real challenge in empirical economic analysis to draw a clear line from a president’s actions and the sorts of deteriorations we document above. Not this time.

That’s obviously bad news, but it’s also the case that if the cause of damage is this clear, there’s a chance that at least some of it could be reversed. Were the president to simply declare victory in the trade war and reset tariffs back to where they were on Jan. 20, it would likely cause markets to rally at historic rates and recession probabilities to decline. Of course, there would be no actual victory, but when has that mattered to Trump?

If they do not reverse course or, most likely, continue to muddle along with conflicting plans by the hour—what they’re now calling, in a phrase that would make a Soviet propagandist blush, “strategic uncertainty”—the damage could be long-lasting and severe.

It takes generations, if not centuries, to build the trust in America that we see deteriorating in the market data presented herein. There’s still time to reverse the damage, but no one can feel confident that this administration will do so.

Jared Bernstein is the former chair of President Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers. Ryan Cummings is chief of staff at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

You said Trump has "thoroughly squandered his inheritance of a strong economy." Trump has squandered every inheritance he ever received and then some. That is all he knows how to do...squander. He has squandered his entire life. That Republicans shut their eyes to this fact is why we are where we are...a great democracy being squandered at the hands of one of the worst squanderers in the history of our nation.

“There’s still time to reverse the damage, but no one can feel confident that this administration will do so.”

And…..the American people voted to bring this upon themselves?!? Does not make sense——What must the rest of the World think about Americans? Can’t be good!