There was more to Paul Reubens than Pee-wee Herman

A fascinating new documentary examines the fraught relationship between the intensely private actor and his better-known alter ego

"I don't want this to be a legacy movie," says Paul Reubens in the opening shot of Pee-wee as Himself, a documentary that was well into production when he died in 2023. Completed posthumously, the two-part film is in fact, “a legacy movie,” a fascinating, heartbreaking exploration of the thorny relationship between an intensely private artist and his famous alter ego.

Reubens remains best known as Pee-wee Herman, the bow-tied manchild he played in the sleeper hit Pee-wee's Big Adventure and the kitschy Saturday morning kids’ show Pee-wee's Playhouse. Out of both a fierce commitment to his craft and an intense desire to protect his personal life, Reubens also embraced the Pee-wee persona in public, almost never granting interviews or making appearances as himself. In the days before the internet, this meant that millions of fans, especially children, assumed that Pee-wee was a real person.

That is until 1991, when Reubens was arrested for indecent exposure at an adult movie theater in Florida, and the meticulously constructed wall between Pee-wee and the man who created him came tumbling down in a flurry of cheap late-night jokes. Reubens was the first of many bystanders caught up in the scandal machine of the '90s, along with people like Pamela Anderson and Monica Lewinsky, whose personal foibles were exploited for tabloid fodder. For Reubens, the nightmare resumed a decade later, when he was arrested on trumped-up obscenity charges related to vintage erotica.

Though he staked a partial comeback later with a Broadway show and Pee-wee movie produced by Judd Apatow, Reubens’ career never fully recovered from the dual scandals. Pee-wee as Himself, which premiered Friday on HBO and is available to stream on Max, is a long-overdue reappraisal of a misunderstood misfit, one that is deeply sympathetic to Reubens yet never descends into hagiography.

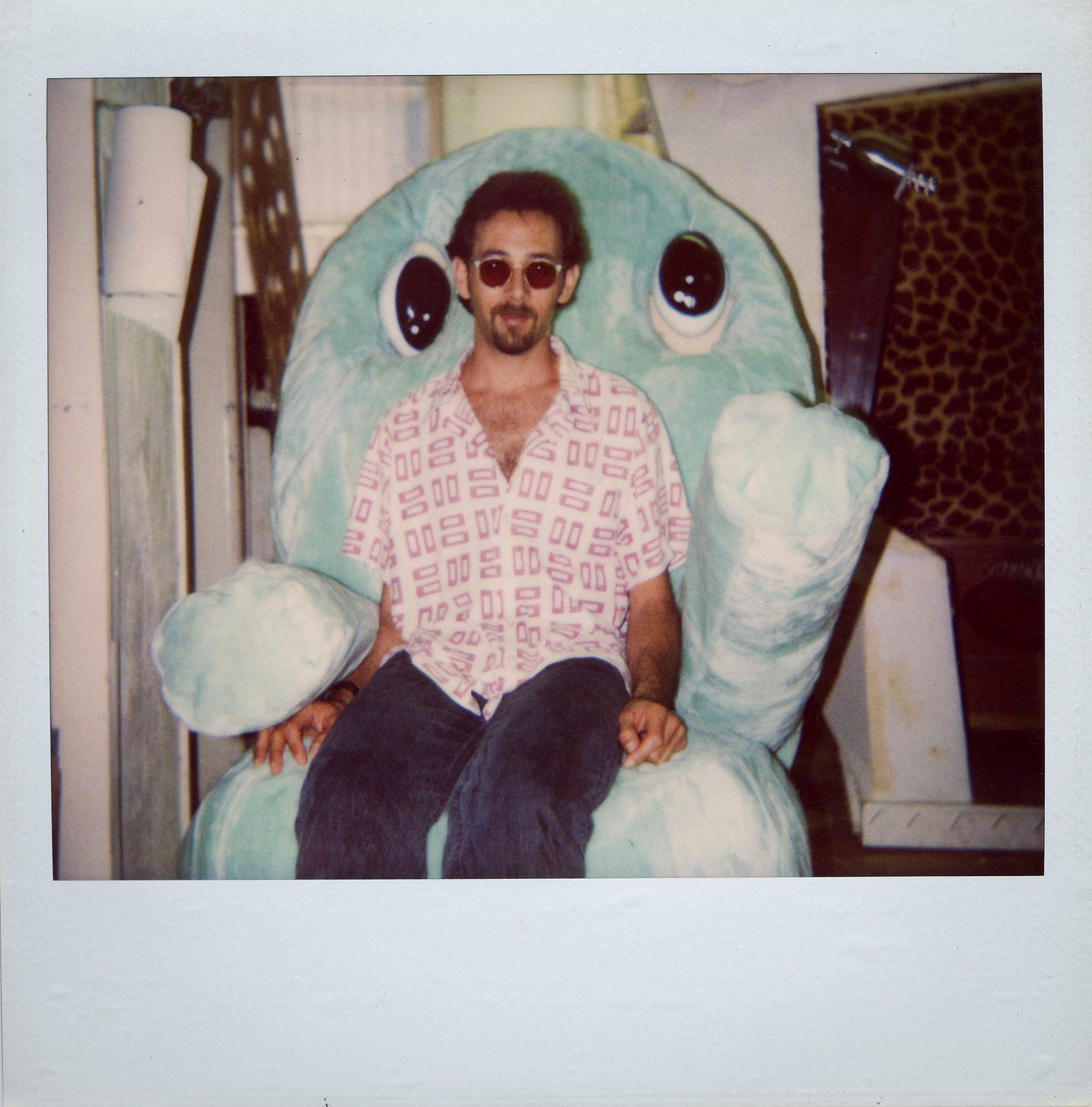

With a running time of more than three hours, the film exhaustively chronicles Reubens' unlikely journey from Andy Warhol-worshipping art school bon vivant to beloved children’s entertainer. Director Matt Wolf, who grew up a Pee-wee fan, is particularly insightful when it comes to explaining why the campy, subversive Playhouse aesthetic was so appealing to kids who felt like outcasts in the conformist '80s. Drawing from interviews with Reubens' inner circle and a vast trove of revealing personal photos, home movies, and student films, Wolf weaves an intimate portrait of an enigmatic performer.

But the most compelling parts of the documentary are the interviews with Reubens himself, who sat with Wolf for 40 hours of often testy conversations about his life and work. Understandably reluctant to relinquish control of his narrative, Reubens repeatedly deflects Wolf’s questions and expresses frustration over not being able to direct the film himself. Though never rude, he comes across as an endearing pain in the ass. The tension between the filmmaker and his subject becomes a powerful thread in Pee-Wee as Himself.

In an almost literal sense, Reubens gets the final word: he stops participating in the project and, soon after, dies after a six-year battle with lung cancer, a diagnosis he never shared with Wolf. Pee-wee as Himself includes a stunningly lucid audio recording, made the day before Reubens died, in which he speaks about “how painful it was to be labelled as something I wasn’t.”

“My whole career was based in love,” he says.

Another major revelation in the film is that Reubens, who never publicly came out despite intense speculation about his sexuality, lived with another man for several years early in his pre-fame days. For the first time, he opens up about his formative relationship with Guy, a painter who inspired one of Pee-wee’s most memorable expressions.

By Reubens’ account, the romance was blissful but all-consuming, blunting his creative ambition. When it ended, he vowed he would never lose himself in the same way again.

"I not only wasn’t going to be openly gay, I wasn’t going to be in a relationship," says Reubens, who threw himself back into acting—and the closet.

In an era when comedy was ascendant in Hollywood, he became involved with the Groundlings, the storied improv troupe. He befriended future stars like Phil Hartman and Cassandra Peterson (a.k.a. Elvira, Mistress of the Dark), and developed dozens of characters, some of them dreadful (e.g. Jay Longtoe, a Native American lounge singer). But one caught on: Pee-wee Herman, envisioned by Reubens as “an aspiring comedian who’s never going to make it.”

Something about the character, with his shrunken gray suit and honking laugh, struck a chord with audiences. When he was Pee-wee, Reubens “felt like I had some kind of a superpower. I can move people. I can cause a reaction." He began to see Pee-wee not as a comic persona but as a conceptual art performance that he carried into real life. (In a very Andy Kaufman-esque moment, Pee-wee even competed on The Dating Game—and won.)

He developed a stage show around Pee-wee — a demented, adult version of Howdy Doody that became a cult hit in Los Angeles. It led to an HBO special, regular appearances on Late Night with David Letterman, and eventually a movie, Pee-wee's Big Adventure, directed by Tim Burton. By the mid-80s, Reubens—or more accurately, Pee-wee—was a huge celebrity.

But it came at a cost.

“By the time I realized that you trade in anonymity and privacy for success, the ink had dried on my pact with the devil,” Reubens says.

The second half of the film looks at the fallout from this “pact,” including his various legal troubles and career woes. Pee-wee as Himself makes it clear that Reubens was the wrongfully maligned victim of pernicious homophobic stereotypes that remain prevalent today. But we also get a sense of how Reubens' rougher edges, particularly his need for control and recognition, factored into his Hollywood downfall.

In all too many celebrity documentaries, access often comes at the expense of objectivity. Filmmakers often face intense pressure to render flattering portraits of their subjects—in some cases, even when they’re dead. Ezra Edelman, who directed the essential O.J.: Made in America, spent five years making a nine-hour docuseries about Prince that has been described as a masterpiece but will likely never see the light of day because Netflix bowed to pressure from the late musician’s estate.

Wolf wisely chooses not to shield viewers from the challenges of making Pee-wee as Himself, yet he never lets his frustration become the focus of the film —a mistake too many documentarians make when they reach an impasse with a subject. It is not clear why Reubens stopped cooperating with the project. Perhaps he resented not being in charge. Or perhaps he knew he was dying and didn’t want to spend any more precious time on camera, relitigating the most painful chapters of his life.

Whatever the case may be, the documentary doesn't suffer as a result of its subject's unexpected death. Instead, it offers an intriguingly incomplete answer to Pee-wee's catchphrase: “I know you are, but what am I?”

RIP, beloved Paul Pee-wee Herman Reubens. ❤️🌷💕

Highly recommend this doc.