The Supreme Court Needs to Double Down on Empowering Lower Courts

Friday’s bombshell opinion suggested a powerful tool for lower courts to hold the Trump administration to account. With birthright citizenship and more at stake, here’s hoping SCOTUS runs with it.

Last Friday, the Supreme Court issued an important decision that effectively blocks Trump’s illegal efforts to deport migrants to a Salvadoran mega prison with no due process. In their unsigned opinion, the Justices also faulted the lower courts for not doing more to hold the executive branch to the law. And yet—in the oral argument on birthright citizenship that also took place last week, some of the Republican Justices seemed unbothered by the administration’s suggestion that it can basically ignore lower court rulings.

If the rule of law is to survive, SCOTUS must empower the lower courts to hold the administration to account.

Friday’s opinion in the due process case, A.A.R.P. v. Trump, is a welcome development. Given the administration’s position that, once people are expelled to El Salvador, they cannot (or at least will not) bring them back, it is essential to ensure that everyone targeted under Trump’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act has received an opportunity to legally challenge their removal. Seven Supreme Court Justices found that the administration’s interpretation of due process—providing people with 24-hour notice in English-only documents that did not remotely explain how to challenge expulsion—was woefully inadequate. Of course, that holding was only necessary because, last month, Republican Justices ruled to pause the lower court ruling that had blocked the AEA proclamation nationwide…clearing the way for the administration to move people to jurisdictions that hadn’t invalidated it, and from there to spirit them away to El Salvador with no modicum of process.

The Justices in the majority last Friday took not only the administration to the woodshed, but also the lower courts that had failed to act. The Court wrote scathingly that “the District Court’s inaction—not for 42 minutes but for 14 hours and 28 minutes—had the practical effect of refusing an injunction to detainees facing an imminent threat of severe, irreparable harm.” The Court emphasized that “[t]he detainees’ interests at stake are … particularly weighty” given the administration’s unwillingness “to provide for the return of an individual deported in error to a prison in El Salvador.”

In other words, the Supreme Court is telling lower courts: do your job. Hold these guys to the rule of law. In a potentially bombshell aspect of the ruling, the Court also suggested how they might do so, signaling to courts that they have the authority to protect all those affected by an illegal policy—not just the plaintiffs in a given case—even without technically issuing a nationwide injunction.

This position could have huge implications for the birthright citizenship case, and perhaps others as well. In the absence of a nationwide injunction that outright invalidates a given policy, Trump’s government has suggested it is willing to enforce policies that a lower court has invalidated—just among people who haven’t successfully sued to challenge them yet. In the context of the birthright citizenship case, I’ve explained what this might look like. Imagine that one baby’s family sued to establish their citizenship and challenge the order denying birthright citizenship. If that challenge were successful, the government could say that while they wouldn’t deny that baby citizenship, they could continue to deny citizenship to other babies…even in the same state or circuit as the decision invalidating the order.

The oral argument in the birthright citizenship case drew this out. Justice Kagan repeatedly asked Solicitor General John Sauer whether he would commit “to not applying its [Executive Order] in the entire Second Circuit” in the event the Second Circuit invalidated the EO in a case brought by one citizen baby. The SG hedged, and after he repeatedly refused to commit to applying lower court decisions, Justice Barrett said “Really?”

One way to address this nonsense is class actions, which allow anyone to sue on behalf of themselves and others in a similar situation. If a birthright citizenship case proceeded as a class action, the government wouldn’t be able to apply its illegal policies to any member of the “class,” aka all babies born on American soil. In the case of illegal deportations under the Alien Enemies Act, all potential victims would be protected.

Here’s the rub: Class certification proceedings take time. Forcing plaintiffs to clear that obstacle would delay anything a court could do to protect those who aren’t actually preparing to appear in court.

That’s where the key part of the A.A.R.P. ruling comes in. The Court declared that the Supreme Court “may properly issue temporary injunctive relief to the putative class,” meaning the Court can protect people who aren’t the named plaintiffs in a case, even if class certification has not yet been granted. The Court emphasized the same is true of lower courts, whether or not they even think class certification is likely.

If, in the birthright citizenship case, the Supreme Court reiterates that courts can and should do this, that would give lower courts an important tool to keep the administration within the law before a court has decided whether to certify a class action. Such a ruling would give lower courts the authority to award what are effectively nationwide injunctions. (If that is what happens in the birthright case, it’s fair to wonder why the Supreme Court even took up the question of nationwide injunctions if it was going to offer a workaround instead—this might be a case of the dog that caught the car).

The Court could also very well make the wrong choice and limit lower courts’ ability to use the “putative class” mechanism to keep the administration in check. In A.A.R.P., after all, the seven Justices justified the preventative procedure by pointing to the government’s position that courts lack any power to remedy wrongful expulsions. That position requires courts to block residents from being wrongfully expelled in the first place to preserve courts’ authority to decide whether the expulsions are even lawful.

In any event, despite the welcome ruling last Friday, the Supreme Court cannot stand up to the Trump administration alone. It needs the lower courts on the side of law. And if it is going to chastise those courts when they don’t act to protect American citizens, the least it could do is to give them the power to actually do so.

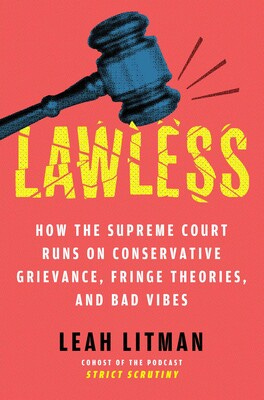

Leah Litman is a professor of law at the University of Michigan and author of LAWLESS: How the Supreme Court Runs on Conservative Grievance, Fringe Theories, and Bad Vibes

I guess the question is, do you really think this Court would do the Constitutional thing let alone the right thing. After all, it violated precedence on precedence in its ruling on Roe, it violated the Constitution in its ruling of presidential immunity, and it violated the Civil Rights Act and the 14th Amendment in its ruling concerning the gerrymandering in a District where Black Americans were disenfranchised from voting for who they wanted for their representative.

As an aside, gerrymandering anywhere is unconstitutional. The Founders put in the Constitution a Congress made up of the Senate so States could be equally represented and the House so that the people could be equally represented. Gerrymandering is an affront to equal representation by the people. It's "taxation without representation".

The Justice Dept. has many tools enforcing compliance that they are not using. And, the media is closed mouth with blinders on about not enforcing compliance. That they are not using them is, in its own right, a crime. Judges who do not use these tools of enforcement should be investigated.