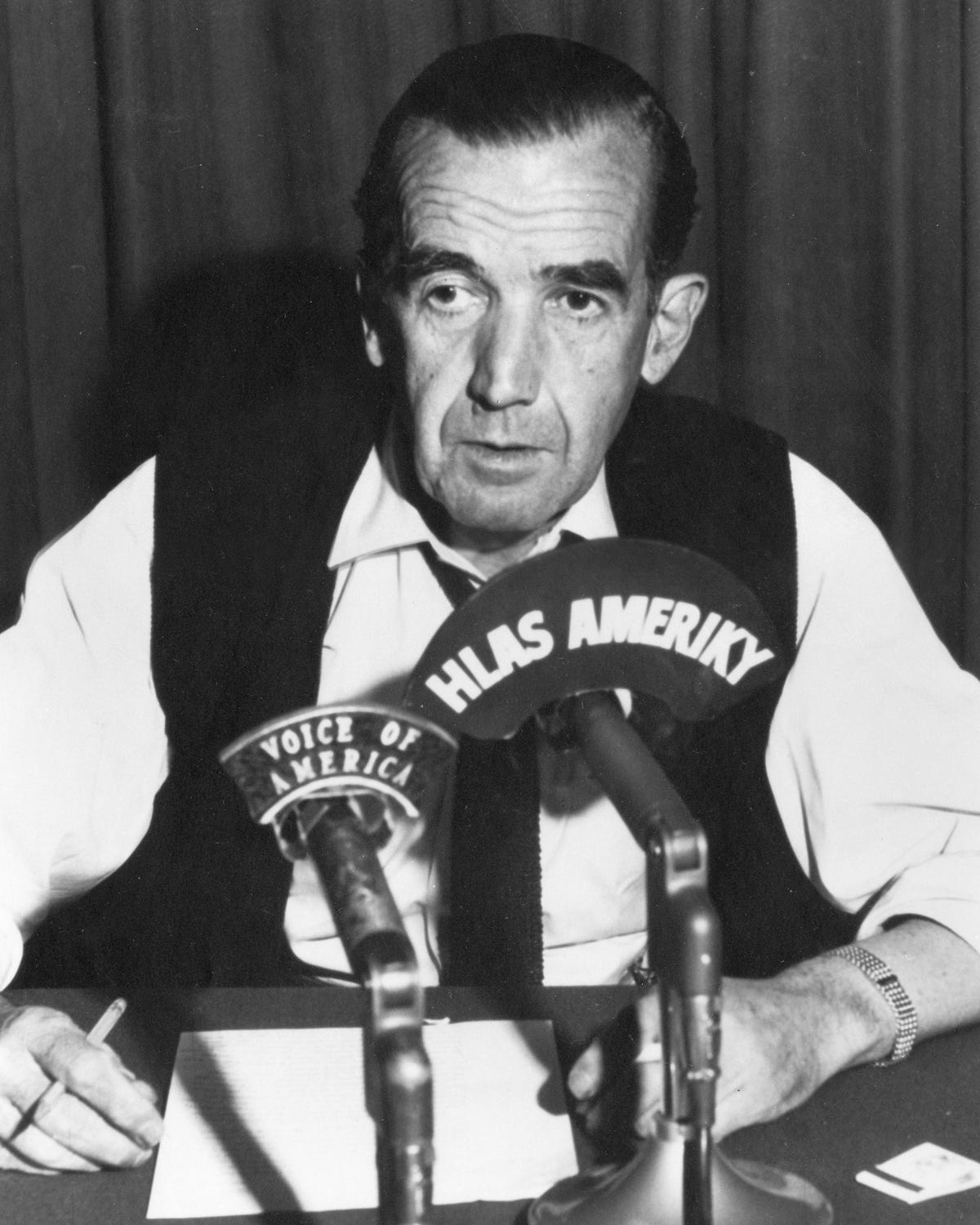

Is There a Murrow in the House?

Edward R. Murrow exemplified a free press unbowed by autocracy—and if American democracy is to survive, we need his like again

By Marvin Kalb

Just as the United States needed the voice and vision of an Edward R. Murrow in the 1930’s when Hitler rose to power in Germany, and in the 1940’s when the Luftwaffe blitzed London, and in the 1950’s when McCarthyism spread fear in America, so too in 2025 does the United States need another Murrow to take on President Donald Trump’s “clear and present danger” to American democracy, once the beacon of liberty for the world, today a nation in deepening chaos and confusion.

But is there another Murrow in the house?

No, not at CBS, nor any network. None has the courage to hire another Murrow. Newsrooms today live in fear of antagonizing a president who is clearly on a warpath against any criticism, justifiable or not. Is the U.S. then slipping into an authoritarian form of governance, in which the executive branch dominates the other two, diminishing them into embarrassingly obedient Yes-men and women? Murrow’s answer would have been a resounding “Yes.” To the day he died, Murrow worried constantly about the weakness of Western democracies to populist pressure.

Murrow started his exceptional career not as a journalist but as a young educator working in Europe in the early 1930’s, hoping to establish an exchange program between European and American scholars. Hitler intervened, blocking Murrow’s hope for transatlantic cooperation. Overnight, it seemed, Hitler converted the Weimar Republic into a fascist state, lighting bonfires of banned books and banishing such writers as Thomas Mann, Martin Buber, and Hans Morgenthau. Against heavy odds, Murrow managed to get some of these intellectuals out of Germany and into professorships at American universities. “The most satisfying thing I ever did in my life,” he later said.

During this time Murrow learned how swiftly a frail democracy could disintegrate into a dictatorship. He once told me the story of a middle-class German family he’d met and, for a time, admired. The father was a lawyer, the mother a teacher. Together, they shared the excitement of Shakespeare, Beethoven and many other wonders of Western culture. Murrow enjoyed their company. Then, in 1938, on a swing through Europe, Murrow visited his German friends. It was a visit he’d never forget. The father was wearing a Nazi uniform and mouthing Nazi slogans, as if he truly believed them. In just a few years, these good Germans had become Nazi fanatics.

Hitler was clearly on the move, as was Murrow, who leaped from education to what his colleague William Shirer called “this newfangled radio broadcasting business.”

His nightly reports about the London Blitz in September 1940 were historic: his microphone picking up the blasts of Luftwaffe bombs, his voice conveying the stubborn gallantry of the British people. President Franklin D. Roosevelt listened to Murrow, as did millions of other Americans, radio bringing the ugly reality of war directly into American homes, a giant advance in journalism’s reach.

On April 15, 1945, with the war finally ending and news of Roosevelt’s death rushing around the world, Murrow visited the Nazi death camp of Buchenwald, keeping an earlier promise to himself. He had heard about these camps and about the Holocaust, the systematic slaughter of Jews. What he saw at Buchenwald—“rows of bodies stacked up like cordwood…thin and very white…terribly bruised…all except two were naked”—was so numbing that for three days he could not “find the right words,” as he later put it, to describe Buchenwald.

If his listeners thought at war’s end that Murrow would now gush with happy stories about family reunions, they were to be disappointed. He often found himself locked in long stretches of silence, “dark, grey memories refusing to give him peace,” as his biographer Bob Edwards observed.

After the war, Murrow returned to New York, where for a brief time he tried his hand at managing the news department but, by September 1947, realized he was better at reporting the news, his true love. He began to appear regularly on radio and television, and was recognized quickly as the pre-eminent broadcaster of his time. In this context Murrow confronted McCarthy, the pre-eminent rabble-rouser of his time, setting the stage for a climactic battle for the soul of American democracy.

To know Murrow was to know that he had emerged from the war with one jarring, depressing belief: that if Germany, a highly “civilized” country in central Europe, could produce such a raw, cruel evil as Hitler’s fascism, then so too could other civilized nations, including the United States, produce their own iterations of evil. It became the inescapable responsibility of every citizen to stand up, unafraid, and confront that evil. For Murrow, McCarthyism was evil. He had to confront it.

The Cold War set the ideological framework, and the junior senator from Wisconsin led a personal crusade against the “communist threat.” He conducted Congressional investigations into “communist infiltration” of Hollywood, the State Department, and the Army. He suggested, without evidence, that high-ranking officials such as General George Marshall and Secretary of State Dean Acheson were somehow helping the communists engage in “subversive,” “anti-American activity.” In this way, McCarthy spread a malignant fear that terrorized everyone, discouraging dissent, stifling criticism. By early 1954, McCarthy was so powerful that, according to a Gallup poll, 46 percent of the American people “approved” of his effort. Among elected officials, only President Dwight D. Eisenhower enjoyed a higher approval rating, and not by much.

Murrow began to dig deeply into the McCarthy challenge to democracy, teamed with the legendary producer Fred Friendly. He covered McCarthy’s hearings, speeches and interviews, in the process producing a run of revealing broadcasts that focused on McCarthy’s lies, exaggerations and distortions.

Finally, on March 9, Murrow decided the time had come for an unafraid point-by-point dissection of McCarthy’s rhetoric and actions. “We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason,” Murrow declared. “The actions of the junior senator from Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay.” Murrow believed it was his “responsibility” as a “citizen” to stand up to McCarthy. Few others apparently had the courage.

Murrow closed his memorable broadcast by quoting Shakespeare. “Cassius was right,” he said. “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars but in ourselves.” He was trying to wake up a frightened people.

He succeeded. The public’s response was overwhelmingly positive. McCarthy’s approval rating dropped dramatically from 46 to 32 percent, and it never recovered. The Army-McCarthy hearings only added to McCarthy’s distress. GOP Senators, who had been frozen into fearful silence, suddenly found their voices. They stripped him of his power to chair his investigations and voted their disapproval of his actions, though gently. Still, for the GOP, these were bold steps, and McCarthy, as both a politician and a movement, then faded into oblivion.

In my conversations with Murrow a few years later, it was clear he did not wish to talk about his role in the unraveling of McCarthyism, but he was always eager to discuss his definition of American democracy. Two pillars supported this “precious” concept, he said. One was “the sanctity of the courts,” and the other was “freedom of the press.” So long as both of these pillars remained strong, then so too, in Murrow’s judgment, would American democracy. But should either wobble, as now seems to be the case, then democracy itself will wobble and ultimately collapse.

Marvin Kalb, CBS’s first diplomatic correspondent, Murrow professor emeritus at Harvard, is author of the recently-published A DIFFERENT RUSSIA: Khrushchev and Kennedy on a Collision Course.

Marvin Kalb, I haven't heard from or about you in ages. Thank you for this illuminating and timely reminder of what journalism SHOULD be all about. Edward Murrow was fearless in the face of McCarthyism. More Edward Murrows are needed badly.

Jen & Norm have already started, but many more are needed. Too bad none of the owners of the MSM have any balls.

Harrowing but wonderful. Profound thanks to The Contrarian for reaching out to Professor Kalb.