By Shirley Atkins

A middle-aged Black woman from the Mississippi Delta, is an example of a troubling and preventable reality. When her child aged out of Medicaid eligibility, she lost her own coverage, cutting her off from regular access to health care.

Without insurance and lacking clear information about the importance of follow-up care, she missed early warning signs of gynecological abnormalities. She faced a difficult decision, and ultimately, she did not see a doctor for her symptoms because of financial constraints. This resulted in a preventable hysterectomy, a procedure that likely could have been avoided with timely medical intervention. Her story underscores a far-reaching crisis: Mississippi’s continued refusal to expand Medicaid has left thousands of women without access to critical health services, exacerbating racial and economic health disparities.

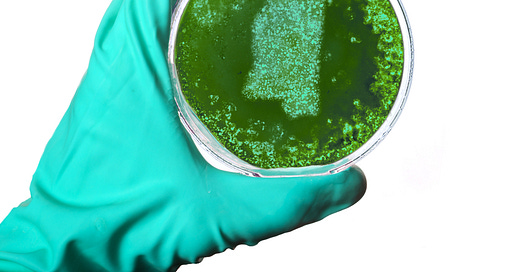

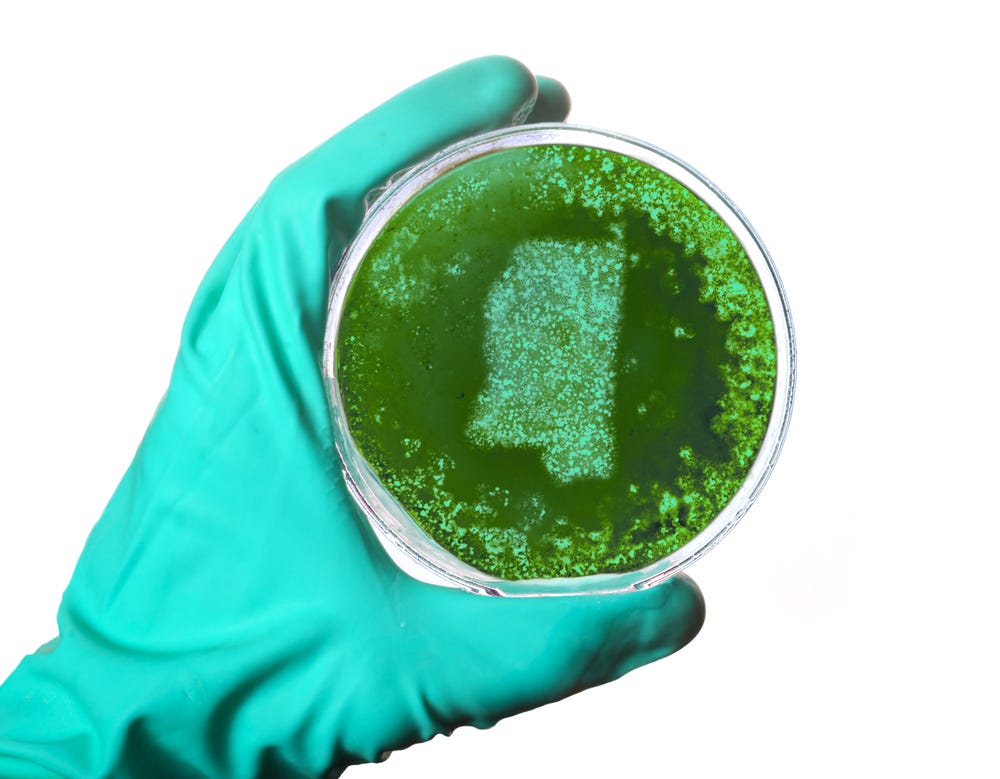

The HPV vaccine is a crucial preventive measure against cervical cancer, yet, in the Delta, knowledge about its importance remains patchy, particularly among Black women who have limited access to health care providers thanks to the alarming rate of hospital closures across the state.

Although many women get regular pap smears, without proper guidance on the HPV vaccine's role in cancer prevention, opportunities to prevent cervical cancer are often missed. This gap in preventive education leads to advanced cases of cervical cancer that require costly and invasive treatments, deepening the economic strain on affected individuals and their families.

Further, potential Medicaid cuts threaten to deepen this crisis. These cuts would make it even harder for low-income families to access preventive care, forcing more women to delay or forgo necessary medical treatment. For those who lose Medicaid coverage, access to affordable health care vanishes. The high cost of doctor visits or co-pays for those able to get insurance elsewhere, a shortage of nearby low-cost clinics, widespread hospital closures leaving entire counties without medical facilities, limited public transportation, and long-standing mistrust in medical institutions rooted in a legacy of racism and discrimination compound these challenges. In this environment, cervical cancer is not only a health crisis but also an economic one, burdening families with expenses tied to advanced-stage treatments, time lost from work, and unplanned caregiving costs.

Mississippi is one of 10 states that still refuse to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Medicaid expansion allows states to provide coverage to low-income adults who previously did not qualify. Under the ACA, the federal government covers 90% of the cost of expansion, with the state responsible for the remaining 10%. However, in states like Mississippi that haven’t expanded Medicaid, billions of dollars in federal funding that could be used to provide health care for residents are instead sent back to Washington, D.C. This means that Mississippi taxpayers are effectively funding Medicaid expansion in other states while they and their neighbors remain uninsured. The refusal to expand Medicaid disproportionately harms Black communities, rural residents, and low-income workers who fall into the “coverage gap”—earning too much for traditional Medicaid but too little to afford private insurance.

Tackling this crisis calls for a combination of policy reforms, community investment, and education initiatives. Mississippi must expand Medicaid to ensure that low-income Black women in the Delta can receive consistent, affordable health care. Increased investment in community health clinics would provide Black women in the region with access to free or low-cost cervical cancer screenings, HPV vaccinations, and essential follow-up care.

School-based HPV vaccination programs offer another promising path forward. These programs would empower parents with the information they need to make informed choices while ensuring that more young people are vaccinated before they are exposed to the virus. Such programs are powerful tools in closing health disparities and would deliver a much-needed boost to public health in Mississippi Delta communities.

The Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative (SRBWI) and Human Rights Watch are working to address this need through a regional initiative focused on cervical cancer prevention and education spanning the Black Belt of Georgia and Alabama and Mississippi. In partnership with local community-based researchers and advocates, SRBWI and Human Rights Watch have made strides in raising awareness about cervical cancer prevention. Through outreach and policy advocacy, these researchers and advocates play a pivotal role in transforming their communities’ understanding of sexual and reproductive health and promoting policies that directly improve the lives of Black women and communities.

But more is needed. Without Medicaid expansion, the cycle of preventable deaths and life-altering medical conditions will continue, worsening health outcomes for Black women in Mississippi. Hospital closures only add to the barriers, making access to care nearly impossible in some regions. Mississippi’s failure to expand Medicaid is not unique—it reflects a broader trend across states that have refused expansion, disproportionately impacting rural Black communities and deepening existing inequities in health care access. Expanding access to preventive care isn’t just about reducing cervical cancer rates; it’s about supporting Black women’s access to critical health care services and information. By addressing these gaps, we can forge a path toward a healthier, more equitable future for Black women and families in the Mississippi Delta.

Shirley Atkins is a Community-Based Researcher with the Southern Rural Black Women Initiative, with more than 20 years of experience in non-profit and community-based organizations. Her work focuses on advocating for the health and well-being of Black women and low-income families in rural communities.

While screening for cervical cancer is no doubt important and preventative as well as HPV vaccination other screening is just as important. Mammograms and screening for highly blood pressure, heart disease and diabetes are also important. Black women are more likely than white women to not be diagnosed with breast cancer early enough making the disease harder to treat because it doesn’t get caught at an earlier stage. Rather than focusing on one area we should be focusing on total body health. Recommendations should be tailored for black women as they should be treated as individuals. Whatever works best for them.

Unfortunately, the governors of these states have no interest in the health of their poorer residents. My TX governor should know about the high rate of uninsured but does not do anything to expand Medicaid.