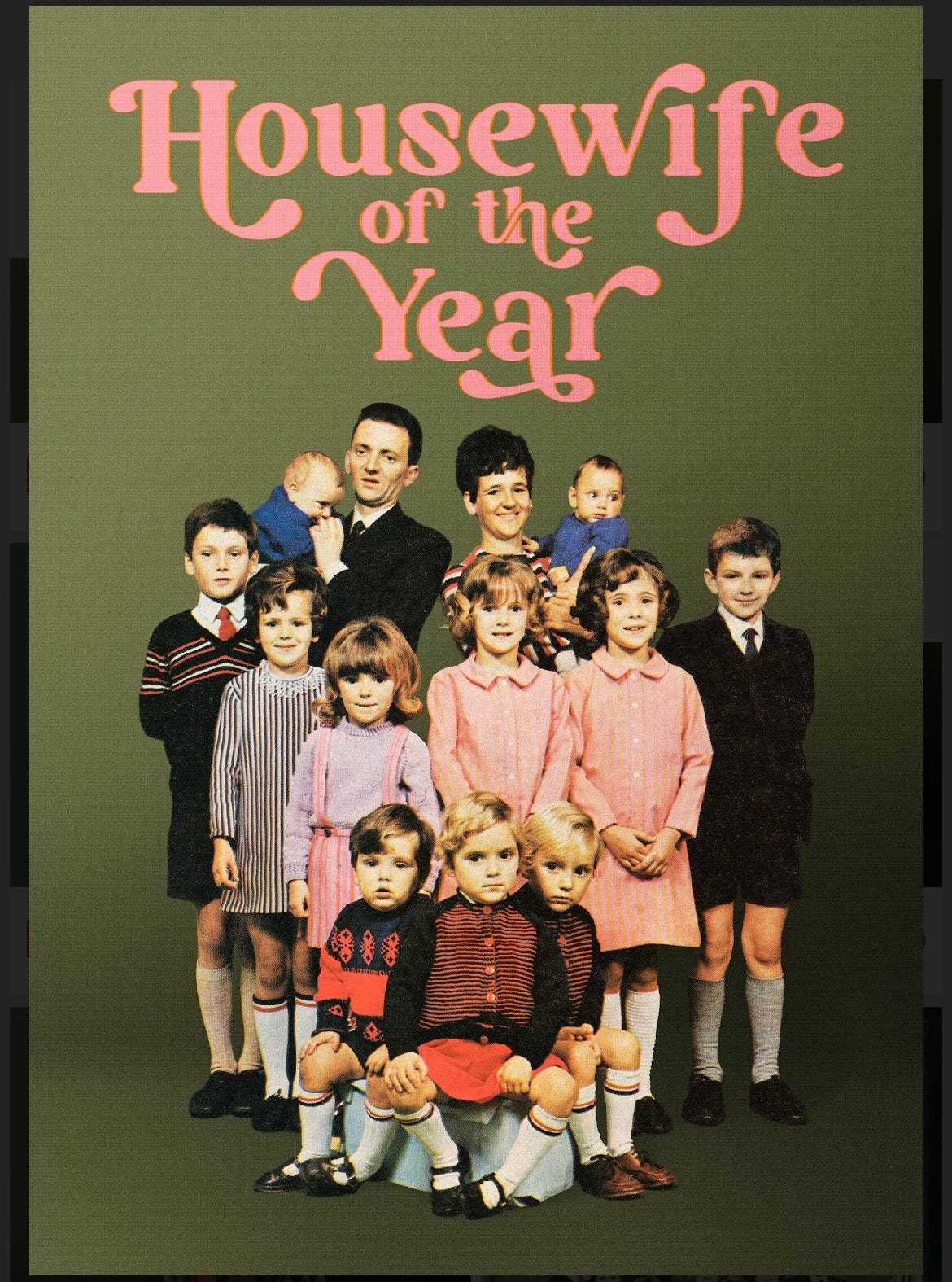

Documentary Spotlight: Housewife of the Year

Contestants recall their experiences in an Irish TV pageant that celebrated traditional motherhood but barely captured the darker reality many women faced at home

Every year from 1967 to 1995, mothers from across Ireland gathered in Dublin to compete in a pageant of domestic prowess known as Housewife of the Year. Televised on national broadcaster RTÉ beginning in 1982 and hosted by Gay Byrne—Ireland’s answer to Johnny Carson—the contest tested their culinary skills, appearance, personality, and civic pride. The winner received a brand new gas stove.

The seemingly retrograde contest is the subject of a poignant documentary, Housewife of the Year, which uses the experiences of 10 former contestants to track the progress of Irish women over the last half century.

These resourceful women, who came of age at a time when the Catholic Church controlled vast swaths of Irish life, recall the hardships they endured in a country where contraception and divorce were once illegal, and where women’s role in the home is enshrined in the constitution. (The opening shot of the film is a caption displaying article 41.2 of the Irish Constitution, which proclaims, “The state shall endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.”)

We hear about the excitement of taking part in Housewife of the Year, but also about the hardships they faced outside their 15 minutes of regional fame: the careers they were forced to give up, the families that just kept growing, the husbands who blew what little money they had at the pub.

The documentary (available to rent on Fandango at Home and Prime Video) focuses on a particular chapter of Irish social history, but will nevertheless feel relevant to American audiences at a time when “trad wives” are all the rage on social media and the pro-natalist movement gains support from prominent conservatives. It offers a timely look at the grim reality of what happens to women when the government endorses traditional gender roles while doing little to ease the burden of raising a family.

“We wanted to explore the gap between what people would have seen on screen, and what the reality was at home,” said director Ciaran Cassidy, speaking by Zoom from Dublin. He became aware of the contest as a child, when a friend’s mom was a contestant.

“I was very young at the time, so I wasn’t that socially conscious. But what I do remember—and what people don’t understand—is that it was a really, really big deal,” Cassidy said. As backward as it might now seem, Housewife of the Year also represented a strange kind of progress. “There was nothing else that featured women at that time,” he said.

The film consists of interviews with former contestants—now elderly but as spirited as ever—and archival footage of the competition, some sourced from VHS recordings.

Instead of using journalists or historians to explain the transformation of Irish society in the latter part of the 20th century, Housewife of the Year gives these women the space to tell their own stories of struggle and perseverance. An occasional news clip helps provide some context, but nothing is over-explained. The contestants look back at what they went through not with anger, but disbelief. As one participant says, “It’s like a dream world—people accepted all these things.”

“What we really wanted was the perspective of the women who were on the stage. That’s the only way you can tell this story,” Cassidy said. “They were laughing about it, but they were also telling you very profound stories about their life and their existence.”

Cassidy and producer Maria Horgan reached out to as many contestants as they could—finding their names in old issues of Woman’s Way magazine and making their pitch via snail mail rather than the phone, lest they be mistaken for spam callers. They sought a range of women from across Ireland—urban and rural, working-class and more upscale.

“We tried to get a balance of stories, and through that, a balance of Ireland,” Cassidy said. “We were fairly confident that we’d find stories, because there’s a lot of stories in Ireland. But I think the scale of it really jumped out at us.”

The documentary showcases an array of women who took part in the contest between the late 1960s and the mid 1990s, by which time it regularly featured women who worked outside the home.

Their stories are often harrowing but relayed with dark Irish wit. Their feelings vary: some women longed for careers, others were content working at home. The film “couldn’t just be a sad story about a generation,” Cassidy said, “because that doesn’t really capture who they were.”

There’s Housewife of the Year 1969, Ann McStay, who married at 20 and had 13 children by the time she was 31. “I didn’t know which end of me was up,” she recalls. She had to feed her kids with stew from a soup kitchen because her husband, “a bit of a drinking man,” spent their money on booze. “The more kids I had, the more he receded into the pub,” says McStay, who later became involved in Labor politics and advocated for birth control.

Another standout is Ellen Gowan, a finalist in the 1984 competition. At the age of 16, she was sent to a Magdalene laundry—a church-run work home for “fallen women.” A local pharmacist developed photos of her cavorting innocently with friends, including a few boys, and tipped off the parish priest.

Years later, Gowan’s husband abandoned their family, leaving her destitute and unable to obtain a divorce. Yet the experience was ultimately positive because, she says, “I was in control for the first time in my life.”

Cassidy says that Irish people tend to be bad documentary subjects because they are too pathologically modest and self-deprecating. The women of Housewife of the Year were different. “They had done live TV in an era when it was unthinkable. They weren’t really spooked by it. They’d already done bigger, madder stuff than this.”

From the vantage point of 2025, it’s easy to sneer at the Housewife of the Year competition (and in fact, plenty of people have). But for several of the women in Cassidy’s film, the contest was an experience that inspired confidence and marked a personal turning point.

“A lot of the contestants spoke very candidly that they enjoyed the process, and they got something out of it,” Cassidy said. “It would have been very easy for us to be binary about it, and just say, ‘Oh, isn’t that terrible?’”

Housewife of the Year recently aired on RTÉ, where it generated conversation about how much things have changed for the women of Ireland over the course of a few generations. While it captures the warmth and resilience of the women who once vied for the title of “Housewife of the Year,” it does not romanticize the past or gloss over what happens to women when their choices are restricted by their government. Viewers in the United States—and beyond—should take note.

“Nostalgia is a dangerous thing politically,” Cassidy said. “I think it’s very easy, with a bit of time, to look back with sepia tones, and to forget what was actually going on.”

Meredith Blake is the culture columnist for The Contrarian.

Sounds fascinating! I haven't watched it, but I like that they women's voices are heard rather than journalists. I am a now retired woman who gave up some career options along the way for family. (Had a very traditional husband, and I knew that going in.) I can see huge value in allowing as much freedom as possible, to both men and women, to choose how to navigate career and family. Each person is unique and there is no one right way to do this. Strict gender roles hurt all of us, not just women.

I am old enough to remember a TV show called “Queen for a Day.” Probably aired in the 1950s. There were women who presented the hardships they faced. Along the lines of “I have 12 children, 6 are in diapers and my husband works in a garage and his overall have greasy stains. I do not have a washing machine which would ease my burden.” There was an Appllausometer that allowed the studio audience to rate the stories for the woman who most deserved to be given the crown to be Queen for a Day (I think she was given a tiara and a cape) and the item she hoped to get, like a washing machine or a wheelchair for her disabled child. Yikes it was warped.