Contrarian recipe of the week: Almond-flour brownies

And a Women's History Month nod to Christine Frederick, who tried to make homemaking more efficient for women.

Christine Frederick stood over a sink of grimy dishes in the kitchen of her Long Island home counting silverware, plates and glasses sometime around 1912. After an evening meal, she found herself facing down a pile of 48 pieces of china, 22 pieces of cutlery and 10 cooking pots and utensils.

Ms. Frederick was not your ordinary housewife. She was one of the leading efficiency scientists of the early 20th century, and with near-religious fervor, she promised to liberate housewives from drudgery and make their time doing housework more productive. Inspired by Henry Ford and his new automobile assembly line, she applied similar techniques to the act of dishwashing.

First, she changed her drainboard from the right- to left-hand side of her sink, and then with engineering precision, she began to wash the dishes:

“I pick up a plate with my left hand, scour it with the cloth held in the right hand, and lay the plate on the tray with my left hand, without changing hands or passing my left arm across my right arm. My left hand is capable of repeating the “laying-down motion” very fast and very easily, while the right hand never drops the cloth, but scours one dish after another rapidly.”

By Frederick’s calculations, use of her dish-washing technique could eliminate drying three acres-worth of dishes a year.

Frederick was part of the scientific management movement known as “Taylorism.” Frederick W. Taylor, a mechanical engineer with stopwatch in hand wherever he went, analyzed workplaces to find the most efficient way to complete a task. Every step saved, every motion modified for ease and efficiency could benefit the worker and would definitely benefit the factory owner. Taylor’s goal was to ensure American industry prospered, and one of his clients, Henry Ford, surely did. Thanks to the time-motion studies done by “Speedy Taylor,” as he was known, Ford’s assembly line purred along: Car manufacture at his Highland Park, Mich. plant went from a 12-hour process down to a measly 1 hour and 33 minutes, start to finish.

The Second Industrial Revolution and The Progressives

These time-motion experiments began with the Second Industrial Revolution. A quick history refresher: The first Industrial Revolution began in the late-18th century and slowly shifted society from an agrarian focus to an urban one. Before this, a woman on a farm in, say, central Massachusetts might have to spin and weave her own cloth, but the Industrial Revolution made low-cost mass-produced goods available. She also might leave the bleak future of farm life behind her and move to a mill town, such as Lowell, and start work in one of the cloth-making factories, where she’d work even longer hours than on the farm, and eventually go on strike for better wages.

Similarly, the Second Industrial Revolution, in the early 20th century, saw new job opportunities for men and women and the introduction to daily life of electricity, cars and important household machines that upended daily existence for many. Much of the technological innovations that occurred still impact our lives today, including the refrigerator, electric iron, dishwasher, vacuum cleaner and, my personal favorite, the toaster. Advancements in science and medicine, the rise of nutrition science and home economics, plus exponential growth of mass-market processed food (Jell-o! Velveeta! Ritz Crackers! Oreos! Marshmallow Fluff!) would transform daily life. The implications of these changes on the role and the experience of women over the next 100 years would be monumental.

Progressive-based movements led by social reformers, home economists, scientists and architects began in the late 1890s, centered around suffrage, nutrition, health and child-rearing. Their efforts brought new attention to the role women could – and some would insist should -- take in society, and they played an important part in changing attitudes towards housework.

The Progressive housekeeping movement was directed squarely at the white middle class. Reformers saw the “professionalization” of everyday activities by housewives as key to change. Theirs was a simple and direct message that was spread from church to ladies’ magazines to the National Congress of Mothers (the precursor to the PTA) and to advertising: Women were in charge of the house. Domesticity was a virtue. Middle-class and upper-class white women were encouraged to use their privilege and position (and newly found free time) to help those less fortunate. Housewives were motivated to address the most pressing needs of society, among them poverty, child labor, women’s work, and, to a lesser extent (but no less worthy in their eyes), the “need” to Americanize new immigrants.

Efficiency experts such as Frederick were dedicated to the cause and spread the word through magazines, speeches to women’s clubs and by appearing as spokeswomen in advertisements for home goods. The main pulpit for Frederick’s message was Ladies Home Journal magazine, where her housekeeping column began appearing in 1912. At the time, the Ladies Home Journal was the most widely read magazine in the United States, with 1 million subscriptions in 1903. (It was popular not only with women, but with men: It was the third most requested magazine by soldiers during World War I.) Both Frederick and advertisers realized the power of her reach, and soon she was testing newfangled household equipment in her country home, where she turned her actual kitchen into a test kitchen and received regular deliveries of the latest stoves and other household equipment for trial. She became a one-woman Good Housekeeping Institute (Good Housekeeping magazine’s own testing division had started in 1900).

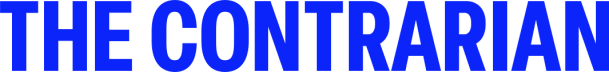

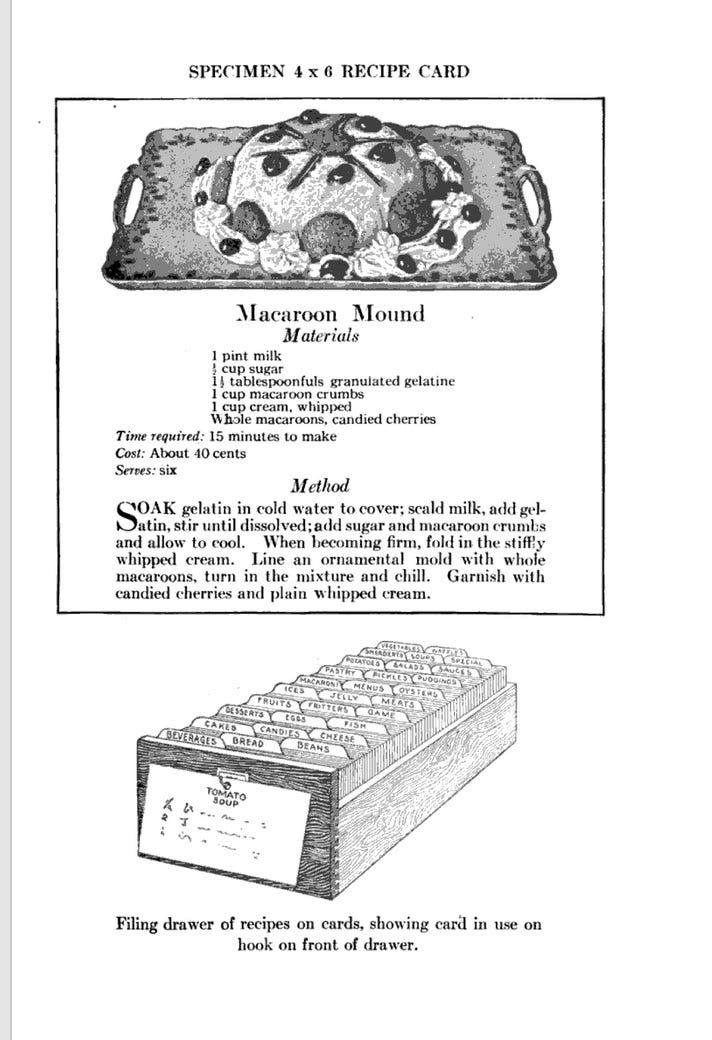

Frederick’s home-motion studies of women as they cooked, served food and washed dishes inspired new ideas in kitchen design detailed in her popular book published in 1913, “The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management.” With efficiency as the beacon of light shining into the dark, dank drudgery of middle-class housewifery, she focused her attention on improving the “fundamental” daily steps of cooking and cleaning. By shopping for modern kitchen equipment, they could help themselves and the American economy. Frederick’s message was clear in her book and her Ladies Home Journal columns: Do your part as consumer, and freedom from drudgery can be yours.

Without looking them up (honor code!), can you guess the order in which these industrial food products appeared on the market, from earliest to latest? The first three people to answer correctly will get free year-long subscriptions to my Substack for themselves or a friend! DM me your answers.

Jell-o

Velveeta

Ritz Crackers

Oreos

Marshmallow Fluff

Today’s brownie recipe is naturally gluten-free, which I know will please many of you. I have been on a quest to find the perfect brownie recipe. There is no such thing, of course. Especially in a world where one day you might crave a fudgy brownie and the next need a cakey one. All my brownies however must be chocolatey: densely, richly chocolatey. Why else do we play this game?

If you couldn’t care less whether something is gluten free or not, fear not. The use of almond flour adds tenderness and protein and makes these delicate, but not wimpy. The almond flour might add a small amount of texture, but nothing any child I know has noticed. Maybe it’s because they are so deeply chocolatey.

Did I mention they can be ready in next to no time?

While the butter is melting, assemble all your ingredients on the counter. Measure, measure, measure. Mix, mix, mix. Add chocolate chips, add more chocolate chips, add a few more chocolate chips, and about 30 minutes later you will have exceptional brownies.

Five-Minute Almond Flour Brownies

Yield: 16 small brownies or 8 larger ones or 1 really big one

What You Need:

5 tablespoons (71 grams) unsalted butter, melted

1 3/4 cups (347 grams) granulated sugar

1 teaspoon kosher salt

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

3/4 cup (64 grams) cocoa powder

3 large eggs

1 1/2 cups (144 grams) almond flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 to 1 1/2 cups chocolate chips (Go on. Don’t measure. Just pour.)

What You’ll Do:

· Heat the oven to 350 degrees F. Spray an 8 x 8-inch baking pan with Baker’s Joy (what I use), or grease with butter.

· Melt the butter in the microwave in a medium bowl. Stir in the sugar, salt, vanilla, cocoa and the eggs until well blended. You don’t want that slick, the-eggs-aren’t-totally-mixed-in look. Shiny, yes. Slick, no.

· Add the almond flour and baking powder. Stir to combine. Pour in the chocolate chips and mix.

· Spoon the ingredients into the prepared pan. Spread the batter evenly to the edges.

· Bake for 30 to 40 minutes until no longer jiggly in the middle, aka, the brownies are set and a toothpick comes out clean. If you’re worried that the edges are getting too dark, cover the pan loosely with aluminum foil and drop the temperature in your oven to 325 degrees.

Remove from oven and let cool on a rack. Resist the urge to eat them burning hot out of the oven as the flavors will not be as good. If you’re lucky enough to have leftovers, freezing them is a-ok.

Note: This recipe is adapted from the King Arthur Baking Company’s incredible recipe database. My tweaks are slight: more salt, more vanilla and chocolate chips.

Welcome to all my new followers at The Contrarian. It’s an honor to be part of this group. For those who don’t already know me, I am a journalist, but also a trained chef and podcaster. I host The Secret Life of Cookies podcast where I interview notable people (from Senator Barbara Boxer to E. Jean Carroll to The Contrarian’s own Joyce White Vance) and we talk about what’s going on in politics, culture, and the world—all, yes, while baking. And, of course, I have a Substack.

NB: Marissa here: The recipe is adapted from the King Arthur Baking Company’s incredible recipe database. My tweaks are slight. More salt, more vanilla and chocolate chips.

I am reminded of a conversation about household labor saving machines with my mother and grandmother maybe 70 years ago. The most transformative, my grandmother said, was the washing machine. I am sure she was referring to the wringer type.